What was Life like in the Workhouse?

“Going up the Lisburn Road” in Belfast was a sign that your family had exhausted all other avenues and only one choice remained - the workhouse. Making the decision to present yourself at the entrance block of the workhouse was one that was designed to be shameful. You knew life in the workhouse was going to be dire. You knew you would be separated from the rest of your family. You would all be deemed “paupers”, segregated into different classes, dressed in workhouse uniforms and expected to work hard in return for shelter and food.

Life in the workhouse was designed to be tough. It wasn’t meant to be pleasant or easy.

First of all, you had to gain admittance. The Board of Guardians who ran the workhouse met once a week to decide on cases. If you timed your arrival well, you might be admitted on the day you turned up. If you missed the meeting, you would have to wait in the entrance block until the next one.

In England workhouses had been introduced earlier and the overseers of the system found that struggling families often dropped off one or two members (usually small children or elderly relatives) at a workhouse to ease their financial burden. When things improved, they came and picked them up again. In order to prevent this happening in the Irish system, the government actually had it written into the Poor Law that whole families had to apply together.

Entering the Workhouse

If you were successful, you were then prepared and moved into the main building. You would be washed and deloused. Your clothes would be taken away and you’d be given a workhouse uniform. You would be put into a category according to sex, age and physical ability. Every class was kept separate from the other, except for children who mixed during school lessons and those under the age of 2 who remained with their mothers. Children aged 2 to 7 were granted “reasonable allowances” of time with their parents. This could be interpreted in various ways.

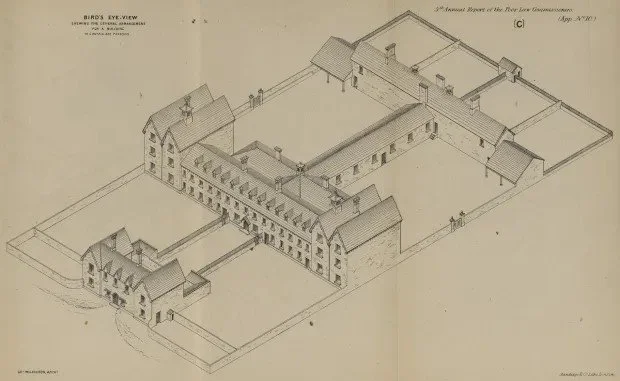

George Wilkinson’s Workhouse Design

The whole building was designed with this separation in mind. The Irish workhouses were all designed by one architect, George Wilkinson. He used the “architecture of deterrence” in drawing up the plans. You slept in dormitories with your class. The building was split between male dorms on one side and female on the other. You ate in the dining hall with your class. You worked in separate work yards with your class on opposite sides of the building.

Wilkinson’s plan

In order to use the space efficiently in the dormitories wooden platforms were used instead of beds. You might be able to get a straw mattress or a blanket in the winter.

Limavady Workhouse dormitory - the radiator is a modern addition, these rooms were not heated.

Work

The clue was in the name and the day to day routine had to involve work for all who were able. The physical work was designed to be monotonous and demanding, often the same kind of work that prisoners were expected to do.

The women were employed in the same activities as women in the Antrim County Jail - needlework, knitting, spinning, washing and domestic work. The main activity was picking oakum. Picking oakum involved taking huge old ropes and separating the strands by hand so that the fibres could be reused. This was repetitive and dull work but it was also difficult. Breaking down tough ropes could lead to multiple cuts on the hands and there were complaints of too much blood being on the resulting fibres.

Oakum found during excavation at Enniskillen Workhouse

Male paupers had to break animal bones to turn into fertiliser and there were specific yards for stone breaking. Stones would be broken down into smaller stones which could then be used or sold for construction work. Obviously you needed a certain level of fitness for this demanding work.

Both sexes were involved in domestic work and producing articles for use in the workhouse. Sometimes these articles would be sold to other workhouses. For example, stockings made in the Belfast workhouse were sold to the Rathdown and Newtownards Unions in the 1840s.

A corn mill was installed in 1847 and any profit was put toward union funds.

Diet

Meals were strictly regulated and the class of the pauper determined how much food they received. Most workhouses served two meals a day, some in the north offered 3. Belfast refused to adopt any of the proposed dietary plans from the Commissioners and instead introduced their own plan.

Breakfast consisted of stirabout, a type of porridge, and milk. Dinner was potatoes or bread, sometimes soup.

Tender for food supplies for Limavady Union

The Commissioners said that the Belfast diet was “too abundant”. Their main issue was giving paupers soup two days a week. The Guardians successfully argued that soup was a typical meal for the poor in Belfast. This soup would have been made of whatever vegetables were in season along with animal bones and, occasionally, barley.

The Belfast workhouse was quite flexible when it came to altering the diet, especially when there were local shortages of certain foods. When potatoes were unfit, the workhouse Master substituted brown bread or soup. This was again unapproved by the Commissioners. They constantly reprimanded the Guardians for providing greater quantities of food than in other unions. To put this into context, Londonderry Union was reprimanded in May 1845 for providing such low amounts of food to the point where their inmates were malnourished.

Belfast was also the first Union to hire a cook to prepare meals instead of the paupers themselves. Belfast was an anomaly within the workhouse system in the early years – it was constantly trying to increase the quantity of food and improve the quality of the diet.

Leaving the workhouse

For a lot of people, entering the workhouse was a long-term solution. Certainly in the early years, families often entered the workhouse and never left. However, there were different ways one could leave.

An extended family member could come to claim someone. A job offer could be received for the breadwinner of the family. Sometimes families decided to emigrate and had help from either the Union or from various charities. The Guardians knew that a large group in the workhouse were able-bodied and unemployed adults so they made strenuous efforts to find work opportunities. By getting one job for an adult, a whole family might be able to leave the workhouse. This wasn’t just to improve the family’s circumstances, it also reduced the financial burden on the workhouse.

One pretty unique example in February 1847 was Thomas Gordon. Gordon was a blacksmith and had entered the workhouse with his family after his leg was amputated and he could no longer work. A memorial signed by ratepayers was presented to the Guardians asking for a wooden leg for Gordon so he could support his family. The Board agreed and Gordon was later discharged with a new wooden leg. His whole family was no longer reliant on the workhouse.

Sketch of a pauper with a wooden leg from the 19th century, Wellcome Images

For many people in the early years of the workhouse, deciding to leave was not a decision taken lightly. The reality was that many would only leave the workhouse through death. Later in the nineteenth century, the ways in which people used the workhouse began to change and it became a place of casual accommodation. People checked themselves in and out as and when it suited them. For the first few decades however it was a longer-term stay.

To read more about what happened to those who died in the workhouse check out my previous articles on the graveyards of Belfast and the workhouse burial ground.